Fifteen Generations of Rowlands

Chapter One continued: 1870 – 2017

Rev. William John Rowland (1844 – 1921)

I have a photograph of my great–grandfather; middle- aged, bearded, balding and rather thickset with staring hollow eyes. By then he would have been in his living as Vicar of Stoke-sub-Hamdon, Somerset. The 1891 census shows him there aged 45 with his second wife Maggie Hobden (42) her sister or mother Catharine (62) and his sons, Sydney (19) studying medicine at Downing College, Cambridge, and William (19) described as a bank clerk in the army, and their daughter Beryl aged four. It is likely that his third son Cecil, and daughter Agnes were away at school. The family was supported by a cook and two domestic servants, and so for a country vicar lived in some style. He then had a private income of £600 p.a., about £50,000 now. Ten years later in the 1901 census, the family is still there, but just with the younger children, Beryl (14) and Winifred (7) and one domestic servant.

He was born on 25th January 1844 at Forest Hill, Sydenham and would have grown up in the extensive household of Alexander William Rowland. His elder brother died at the age of eight and his next elder brother Henry Edward, as the “eldest” son was destined to inherit the family business. So from the usual activities for second sons, William John went into the Church. After school at Aldenham, he took his BA at Worcester College, Oxford, in 1868 and his MA in 1870.

At this stage he would have received his inheritance from his father of about £500,000 now, so would have had a comfortable standard of living.

Following Jane Austen’s maxim about young men with private incomes, he soon took a wife, Anne Ellen Domville. (Tree 4) The 1871 census shows them living at Fox Cottage, Mylor, Cornwall, where he was the Curate of St Peters’, Flushing, with one servant. Anne was just eighteen.

She was the daughter of Colonel Edmund Charles Domville, from a rather more upperclass family than the Rowland’s with their trade background. Col. Domvillie’s brother was Dr. Henry Jones Domville (1818-1888) General Inspector of Hospitals and the Fleet and Honorary Physician to Queen Victoria. They also had some skeletons in the cupboard. The 3rd Lord Santry married Bridget, the daughter of Sir Thomas Domville. Their son, Henry Barry, the 4th Lord Santry, a member of the Hellfire Club, murdered a passer-by in a drunken brawl at the Palmerstown Fair in 1738; apparently too drunk to draw his sword, Santry swore he would kill the next man who spoke to him, which he did! He was convicted, and commissioned an expert swordsman from France to carry out his execution, swiftly and painlessly. However he was pardoned, losing his title but not his estates, because his uncle threatened to cut off Dublin’s water supply if he was executed. This uncle, Sir Compton Domville inherited the estates. He carried on the barmy tradition by banning his nephew, Henry Domville from Santry Court for marrying a Margaret Bell in Lisburn Cathedral; her family were in trade. The story goes that he gave Henry £100 and his choice of a horse from the stables before he was banished. Sir Compton also had a horse shot because it did not please him. He later erected a monument to it.

From this Henry’s branch of the Domville family, which moved to Devonshire, came the forbears of Anne Domville. Sir Compton died without male heir and left the Santry estate to another nephew, Charles Pocklington, under a name and arms clause. The estate comprised Santry Court, called a miniature Versailles and some 5,000 acres of farm land providing an income of £17,500 p.a. (now £2 million) It stayed with the Domvilles until 1935 when it became a residential home for people with learning disabilities, rather like Alexander William Rowland’s Champion Hall becoming a childrens’ hospital. In the war Canadian soldiers were billeted there, and it was damaged by fire. Its demesne now forms a public park.

An even more exotic Domville family story has Bridget Domville, King Henry II’s childrens’ nurse, starting the clan on the wrong side of the blanket and giving us royal blood. I have not been able to find any evidence of this.

From this glamorous background, a living in Cornwall with a Curate, albeit a wealthy one, may have been a come down to his young wife. But she promptly bore him a clutch of children, Sydney (1872) at Mylore and William Domville (1873) at Lanlivery, where William John became Curate. In 1872 William John left Flushing; I have a silver salver presented to him by his parishioners “as a token of affection and esteem”.

In 1873 the family moved to livings in India, where Agnes (1874) and Cecil (1877) were born. William John was chaplain at Eccles Estate, Jubbalpore, (1873), Cale Cathedral (1874), Roorkee (1875/6), Meerut (1877/9), Fort William, Cale (1879) and Darjeeling (1880/1)

Perhaps Anne was feeling trapped by religion and children, or maybe that Domville gene erupted. Anyway she eloped with a medical officer, Dr Cornelius John McKenna. This is described in Sir Philip Gibbs’ autobiography quoted below. Footnote 4

After Anne’s departure William John went on furlough (1882/3) and returned to England to become vicar of St Mary’s, Stoke-sub-Hamdon. There was an expensive divorce from Anne; and this also put paid to his preferment in the Church. Hence the rather pained expression of someone down on his luck with his inheritance reduced, and church activities limited to “parish poking” as he put it. Maybe he also resented the comparative successes of his siblings, Henry Edward who sold his share in the family business to his cousin George William. This enabled him to devote himself to the study of the Doomsday Book on which he was a great expert. Alice, a doctor married to Dr Ernest Hart, Editor of the British Medical Journal, Tessie, married to Barham Snelling, editor of the Egyptian Gazette, Fritz, as a solicitor and Henrietta, latterly Dame Henrietta Barnet, as a celebrated social reformer. Certainly he had no time for her socialist leanings; he also objected to her snaffling her sister Fanny’s inheritance. Anyway he had little to do with his Rowland relations and advised his children accordingly. He remarried, Maggie Hobden and had two children Beryl (1887) and Winifred (1894) (Tree 6)

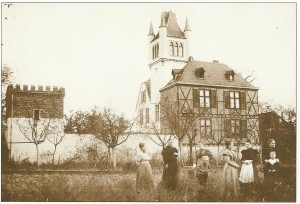

Bedroom at the rectory, Stoke sub Hamdon

where Agnes Rowland may have been

incarcerated by her father.

His daughter Agnes was educated at a convent school in Belgium. As an Anglican, William John was incensed when, not altogether surprisingly she became a Roman Catholic. She met Philip Gibbs through his sister who was also at the convent and they married in 1898. (Trees 7 and 8) Philip and William John became good friends and took a number of continental trips together.

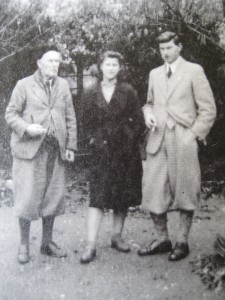

Rev William John Rowland, as Edward VII, with his son Sydney, second wife Maggie and daughters Beryl and Winifred.

In his later years he rather resembled King Edward VII and on one of these trips he once had the Louvre cleared for him on the mistaken impression that he was the King. On another occasion he reacted with an angry “ Belch yourself” to an attendant clutching his arm with an impatient “Roi des Belges“. In a similar vein, I rather like Sir Philip’s story that when taking a horse-drawn cab in Paris, Sir Philip tried to attract the driver’s attention shouting “Cocher, cocher”. But the driver misheard and responded grumpily “ Cochon vous même”.

William John became Rector of Middle Chinnock from 1904-9. He died in 1921. There is a monumental inscription at St Mary’s, Stoke-sub-Hamdon on the North wall of the nave stating “ William John Rowland MA, died and interred at West Clandon, Surrey, Vicar of this parish 1894-1904”. His estate was £654-5s-1d.

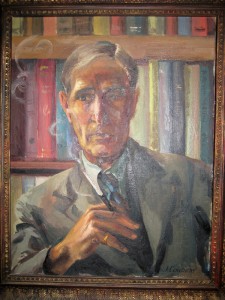

When it comes to writing, I cannot improve on Sir Philip’s description of his courtship of Agnes Rowland, so I will quote his chapter entitled Marriage of Babes from his autobiography, The Pageant of the Years, published in 1946. It was dedicated “with the author’s love to Philip Martin Gibbs and Frances Gibbs (his grandchildren and my second cousins) of the younger generation and to a very small boy named Richard Rowland who looks out on life with laughing eyes and to many small people who are the author’s friends”. My copy contains the inscription “To Richard who may one day read this book by his old friend and playmate “Gung-Gung” Oct 26 1946”. Gung-Gung, my attempt as a two year old at uncle, later became refined to Gungy.

“ I fell in love and three years later, at the age of twenty one, married my love. Her name was Agnes. She was the daughter of a country parson, the Revd. W.J.Rowland, who had the living of Stoke-under-Ham, and afterwards of Crewkerne and Middle Chinnock, down in Somerset, where as I said in the old phrase I went a-courting. Agnes had been brought to our house in Clapham by my sister Helen, with whom she had been to a convent school in Belgium, near to the Ardennes at Paliseul where in the second World War the Americans fought some of their stiffest battles. When I saw her first I knew that all my happiness lay with her, though I hardly dared hope that she she would care for me, because my brothers, Cos and Frank, were so much more amusing and made her laugh far more than I could ever do. She had he gift of laughter all her life, having a merry wit and a sence of humour never killed by desperate illnesses and much spiritual unhappiness in later years.

As a young girl she had a rose-like beaury, and it is among roses that I like to remember her for she tended them in many gardens. I saw her first among roses in the garden of her aunt’s house in Elstree, where, in a white frock which would look very oldfashiobed now, and a big straw hat, she stood with a pair of scissors snipping off the dead blossom from a marvellous show of summer glory. Shyly I went towards her, and saw her laughing eyes, and heard her cry of “Hullo. Pip!”

Her aunt was her father’s sister Alice who had married a distinguished and sinister man named Dr. Ernest Hart.

He was for many years Editor of The British Medical Journal, and stood high in his profession. He was a rich man with a house in Wimpole Street, filled with a priceless collection of Japanese bronzes and porcelain.

For a time he gave house-room to Agnes in return for secretarial service and enslavement, and to Wimpole Street went I in a top hat, tail coat, and striped trousers, when old Hart was well off the premises, and when the footman-he was I thought an insolent fellow-gave me a wink as much as to say “the old man’s out”.

My future father-in-law had another sister who married a remarkable man, more benevolent-though grotesquely ugly-than Dr. Ernest Hart. This was Canon Barnett who, with his wife Henrietta, founded Toynbee Hall in Whitechapel as a centre of life and learning and social welfare in the East End. Afterwards Mrs. Barnett became Dame Henrietta and helped to found Hamstead Garden Suburb in which once I gave a lecture, pleasing the old lady, who was a combination of Queen Victoria and Mrs. Jellyby, with a touch of Becky Sharp, by referring to her as “my amazing aunt”.

My future wife’s relations took me into unknown ways in those years before our marriage. I came to know the life of a country rectory and of many parsonages in its neighbourhood, and of country squires and local characters including some who made a stir in the world of letters, like the three Powys brothers. I came to know intimately and with some affection the greatest character of all – my future father-in-law.

The Revd. W.J.Rowland had been a military chaplain in India. That was why my wife’s first language was Hindustani, and her first memory of life a vision of Cashmere. Being a man of private means he and his first wife had lived in some style out there with carriages and native servants. It had been a gay life, especially for my wife’s mother who was a Domville of Devonshire and a beautiful lady of the old quality, elegant, a little masterful, but easy in her ways with gardeners and grooms and gamekeepers and sextons.

A little too gay perhaps, that life in India. When I knew her afterwards – long afterwards – I understood that as a clergyman’s wife she was out of place. She had no reverence in her laughing heart. She was an incurable flirt. She was witty and, poor dear, a little wicked. One night in England when they had left India for a spell she said good-night to each of her sleeping children, of whom there were four. One of them grew up to be Sydney Rowland, a brilliant bacteriologist and an expert on spinal meningitis, of which he died as a martyr to science, in World War 1.

Another was my wife, then a little girl of seven or so. She remembered a strange glitter in the eyes of her mother who bent over her and gave her a string of beads and then slipped away. She slipped away with an officer in the Indian Army.

I dont know whether my future father-in-law was more stricken by the loss of a beautiful lady or the expense of the divorce she cost him, but I think the latter. He was embittered also by the impossibility of getting promotion in the church, which at that time regarded a clergyman who had divorced his wife and then married again – he married again – as ineligible for ecclesiastical preferment. He was given poor parishes in the depths of Somerset, instead of being made a Canon or a Bishop according to his intellectual ability and ambition.

He was a great scholar in the full sense of the word. I have never met a more learned man, or a man more passionately devoted to study. All his life he rose, winter and summer, at 5.30, washed his face in cold water, and sat down for a couple of hours reading before breakfast. He was always reading, except when “parish poking” as he called it, when he visited the old and sick and fulfilled his duties as a country clergyman, which he did conscientiously but without enthusiasm. He was a fine classical scholar but vastly interested in almost every branch of knowledge, except science. He studied architecture, and could tell the date of any part of a church or any bit of decoration within twenty five years. He read history deeply.

He was a profound student of art and of all its masters. He studied old furniture, porcelain, sculpture, medieval craftmanship. He read vast tomes on the history of Rome and every volume of Frazer’s Golden Bough, and every authority on early civilisations.

But in spite of this scholarship he had a rich sense of humour – very Elizabethan at times – and was fond of a flirtation with any pretty woman, if she had intelligence as well as good looks. He found much food for his humour among the neighbouring clergy, to all of whom he gave nicknames kept dark as a family secret. I remember “Dirty Shirt”, who had a vicarage not far away. His wife was placed in the portrait gallery as “The Light of the Harem”. In a carefully locked drawer of the Vicar’s desk was a manuscript book bound in red leather and filled with most dangerous stuff, but very mirth provoking when occasionally he let me have a glimpse of it. Into this book he wrote squibs, satires, and ironical verse about his relations and neighbours, with occasional sallies into the political field. His sister Henrietta Barnett, and her husband the Canon, were among his most bitter satires.

“Have nothing to do with your relations,” was his constant advice to his family, uttered as an almost daily slogan.

Certainly his brothers and sisters, and nephews and nieces, were a very queer crowd, rather feckless and disorderly. They had all inherited small fortunes from a very rich father who was one of the most celebrated men in England, being none other than the proprietor of Rowland’s Macassar Oil which originated the Victorians antimacassars, on every horsehair-stuffed chair, in every Victorian household. Byron wrote about him in Childe Harold. His name was as familiar as a household word, and his oil was as precious balm to the luxuriant whiskers of Victorian dandies. As a young man he went to Germany and brought back a little German wife whose portrait hangs in my drawing-room now, a pretty and pathetic little lady, childlike and delicate, but the mother of a big family before she died, poor dear. She was of course, my wife’s grandmother, and once Agnes and I, being in the Rhineland, went to find her family “schloss” at Honef-am-Rhein of which we had a drawing. The driver of the car to whom we confided our quest became quite excited and sentimental. He stopped several citizens of Honef and informed them of the object of our journey.

“The Herrschaften seek the Schloss of their German grandmother.” “Ach! That was very romantic. Surely it is the Schloss now inhabited by Herr von Diercksen,” or whatever the name might be.

We were taken to several Schlosses. The driver would stop below a flight of steps and say: “This is the Schloss of your grandmother.” But it was not the Schloss of my wife’s grandmother, according to the drawing we had.

At the fourth time we yielded, and pretended that certainly it was the Schloss and gazed at it with sham sentimentality which satisfied the romantic soul of our German driver. Footnote 5

My father-in-law-to-be inherited a somewhat Germanic character from his little German mother and her ancestry. That may have accounted for the severity with which he brought up his family. His three sons hated him because of his bullying, though he sent them to public schools and spent a lot of money on their education, which greatly reduced his inheritance.

He sent Agnes to a convent school in Belgium, as I have said, for the sake of economy, and then was violently angry when she told him one day she had become a Catholic. He treated her in a medieval way, shutting her up in her room, after denouncing the Catholic Church and all its works.

He even wrote a letter to the Pope, but His Holiness ignored it. It was a long time before he became reconciled to this change of faith, but he had mellowed when I went down to Somerset with Agnes before our marriage.

Every morning before breakfast we joined in family prayers in his study. I can remember the smell of his room – old leather, old books, and the tobacco of many pipes. This combination of scents was heavily stored up in that big study because its owner did not believe in what he called “foul fresh air”. Another saying of his was that he “never drank what he washed in”. He was a great beer-drinker like his mother’s ancestors, and was a big, burley man with a brown moustache and beard and plump fair-complexioned cheeks. I came to like him a great deal and we were always friends, though at first sight of me he told Agnes that I was no match for her, which indeed was true.

He had a passion for foreign travel and after my marriage I went abroad with him several times, mostly to France, staying in Paris and going to the Louvre every day for a couple of hours at least. Once we went as far as the Pyrenees where to my astonishment I saw a real live bear on a snow topped peak. On these journeys he was a good companion, and when we visited cathedrals, and churches, and galleries, and castles his immense knowledge was an education to me.

His second wife was a tiny little lady, very prim and old-fashioned, like a character in a Jane Austen novel. She had been in school in Belsize Park with the Caltrops and Novellos and the Boucicaults.

There she learnt the “use of the globes”, read the letters of Madame de Sévigné and received the “ladylike” education of the time. She also went to all the operas, and when she became an old lady and came to stay with me her greatest pleasure was to remember the enchantment of Verdi, and

Offenbach, and Mozart, and Bizet. She loved music, and played very charmingly even when her little hands were knotted with rheumatism, and when she had to peer through spectacles to see the notes, I made a pencil sketch of her at the piano and it is very like her. She became the mother of two girls. One of whom is now a Reverend Mother, always gay and quick to laugh. I shall have to tell a story about her when I come to the first World War. The other daughter is now the mother of a Saxon-looking young gunner – Adrian Harbottle Reed – who has the scholarly nature of his father and “something of his look.”

In the thirties Sir Philip and his wife Agnes were living at Dibdene, Shamley Green, Surrey. One day she remarked to him that she had just seen a blackbird in the garden with a remarkable resemblance to Aunt Yetta (the family’s name for Dame Henrietta Barnett) Later they learnt that she had died that day.

William Domville Rowland (1873-1944)

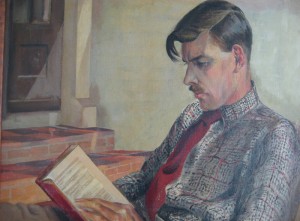

My grandfather looks quite a racey old cove. I have a photograph of him in check plus fours, with the look of Terry Thomas playing a cad. In his time he had several failed careers and relationships. He even died a week or so before I was born.

He probably had all the disadvantages of being accustomed to a high standard of living, but having no inheritance or income to support it. His mother had eloped when he was about nine, and he would have been brought up by a pious, disillusioned and strict father, and latterly by his stepmother. He was sent to Marlborough, but did not go to university. His reports describe him as a “capital fellow” and his leaving reference states “He always bore an excellent character here, and when he left was a trustworthy prefect, exercising a good influence in his house and in the school-none the less because he was vigorous in games!” At the age of 19 he was working as a bank clerk in Cornhill. He then worked for a number of Agricultural Co-operative Societies in Tyrone, Donegal and Warwickshire. According to his half-sister Winnie, he would stick at no job. His aunt Alice Hart lost a lot of money by putting him in charge of some silk mills she opened outside Dublin. Later he became chief reporter on a newspaper near Crick on agricultural and horticultural matters; apparently he had a green finger (not inherited by me) He taught English in Hamburg. In 1906 he went to Liberia, in an official capacity, and was invalided back to Norfolk. He bred rats for his brother Sydney for use in his experiments at the Lister Institute. He became an expert in collecting and selling antiques, including many Nelson relics such as his walking stick and the font where he was baptised.

A failed relationship was with Baronne Henriette de Belgarde, somewhat older than him, a friend of his stepmother’s, who was a writer and translator. In a letter from Winnie (his half-sister), she states “He would marry her, this turned out just as father (William John) said it would, and he left her literally bruised and bleeding”.

She came from a famous European family with family an amazing track record as lovers and mistresses. Roger Bellegarde, the Grand Ecuyer of France introduced his mistress Gabrielle D’Estrees to Henri IV who fell for her and fathered her child, or was it Bellegarde’s? Despite being married to Marguerite de Valois, the King tried to legitimise the child but failed. The Parisians hated Gabrielle who they called the Duchess D’Ordure. She died shortly afterwards giving birth to a stillborn child.

A century or so later Lalive de Bellegarde participated in a celebrated menage a trois with Saint Lambert and her husband Count d’ Houdetot. Chateaubriand stated that this love triangle “was the jaded 18th century married to its manners. It is enough to embrace hedonism in life so that illegitimacies become legitimacies. One feels an infinite regard of immorality because it did not cease, but rather time decorated it with wrinkles”.

Henriette de Bellegarde is also a heroine in Moliere’s Les Femmes Savants. She rivals her sister for the favours of Citandre, who fancies her, but goes off with her aunt instead. Nothing is simple in the Bellegarde world.

In the 19th century Count Heinrich von Bellegarde (1746- 1845) was a distinguished Austrian Field Marshall and statesman and was probably related to Henriette. I have discovered records of a Henriette Belgard born on 16th October 1862 at Gartenpungel, Mohrungen, Ostptressen, Prussia. This fits with her age, about 10 years older than Willie. There is also a record of death of Henriette de Bellegarde on 24th August 1917 at Aberstein, Austria. However, subsequent research shows that these were not our Henriette.

Henriette was born in Paris on 4 February 1858, the daughter of jean Alexander Paulin Niboyet and Caroline Sears. Henriette’s great grandfather Colonel Jean Niiboyet had been granted the hereditary title, Chevalier de Bellegarde, by Napoleon for services in the field.

William Domville and Henriette were married by Licence at St Pancras Registry Office on 16 December 1896. The witnesses were Eugenie de Bellegarde, Alfred Robins and Lucie Bradbury. They were both living at 84 Guilford Street;, he was 23 and she was 33, both described as journalists. Her father, Jean de Bellegarde is described as the French Consul. Henriette is also described as the divorced wife of Julius Rodolphe Erchens. Footnote 6

I do not know how long they were together. In the 1901 Census they were living in Balderton, Nottinghamshire. In 1908 William Domville fathered a child, Lorna, with Evelyn Hariet Waring, so the marriage would have been on the rocks by then. Lorna’s birth certificate gives her mother’s name, and I have not traced any record of their marriage. Lorna called herself Waring Rowland and emigrated to New Zealand and wrote about growing herbs (that old green finger). She died intestate in 1988, her small estate passing to my father and his sister.

The 1911 Census shows Henriette staying with Anne Elizabeth Marriott (private means) with Anne’s mother and a servant. So they had clearly separated by then. Henriette died in Bournmouth, aged 80 in 1940. I have not found records of her divorce.

William Domville married Mabel Louise Bracey on 29 June 1918, when she was pregnant wiith their son Brian. On the marriage certificate he is described as a bachelor, so maybe he was economical with the truth. He referred enigmatically to his three children, Brian, Barry (my father) and Bridget as the three B’s.

Mabel was a district nurse based in Burnham Market, Norfolk, where Willie ran an antique shop called “The Old Curiosity Shop”. After their marriage he obviously intended to live more conventionally; he wrote his holograph Will in 1924, leaving everything to his wife, and never revised it. He was about fifty when he had his three children and by all accounts was a distant father. My father never talked about him. Willie also followed his father’s advice to have nothing to do with his relations, including his father, who died in 1921. It was not until 1924 that he enquired of his stepmother about him. She wrote to him rather testily as follows-

“Dear Willie,

I have heard this morning that you are asking for details of your father’s death. I am writing at once to tell you that he died at West Clandon, Surrey, on April 26th 1921. Had you been in touch with us you would have been informed as a matter of course. A full announcement was in the Times.

His illness was partial paralysis complicated by disease of the bladder and heart trouble. He had every possible attention, a good doctor and male nurse, and was about to be taken to a Hospital of high repute in London to see if an operation were feasible and advisable but he became much worse and died before he could be received. His estate is in the hands of the Executor Trustee. It is a very small one. The income is mine for life, after which the capital is to be divided between his three daughter’s in equal portions. The will was short and simple. There were no legacies.”

In about 1930 Queen Mary drove over from Sandringham to visit the Old Curiosity Shop. Willie’s account of the visit is as follows.

“The Queen has just been in and bought a toy tea set; accompanied by a crowd, Princess Mary, Queen of Norway and two others. She went round and came particularly to see a round table with three scallops on the legs, probably a Scales family table, who owned the original Sandringham Manor at one time and two pieces of white china marked A, probably Augusta, wife of Frederick. She was very keen on some Hochet china, a commemorative Nelson buffet and a sofa.

She stroked Biddy’s hair and said what a lovely child. Etc. Quite a businesswoman while Mother did up the parcel. Burnham poured out to see the Royalty. Guess she will come again. She went all through the Nelson relics and was darned pleased with herself”.

In 1931 Lady Agnes Gibbs (Willie’s sister) wrote to him complaining about having to look after two old mothers. Their stepmother Maggie was senile and placed in a home at Totnes, which was “mighty expensive. She has £2-2s per week so we have to pay the rest. Mrs Mac (their mother) is fractious” and was being looked after by her niece Winnie Churchward at Stoke Gabriel. Both old ladies died in 1932. Agnes passed on half her inheritance of £400 after Maggie’s life interest to Willie.

Another family record is an interesting letter written just before the Second World War from Agnes to her son Anthony Gibbs exhorting him not to send his son Martin to a public school; “of my three brothers two went to public schools and were no good (namely Willie and Cecil, who was last heard of in Rhodesia in 1911) Footnote 7 Sydney went to secondary school and came out on top”. After going to Downing College Cambridge, Sydney worked with Charles Martin at the Lister Institute; in 1905 Sydney was seconded to the Indian Plague Commission and then worked on vaccinations at Elstree. Sydney joined the RAMC in the First World War and died in France in 1917 fro m an infection associated with his work. He was commemorated on a plaque at the Lister Institute. Footnote 8

In fact Martin was sent to public school against his grandmother’s advice. Whilst Martin did well in spite of this, he nearly had a nasty glitch when appearing in the Blue Arrow trial. Of course he was eventually exonerated, having been described in court as someone who would not even park on a single yellow line; but you will have to read all about that in his interesting autobiography, Anecdotal Evidence.

Willie died on 10th July 1944 in Burnham Market. His estate was £569-14.

William Barry Rowland (1920-1998)

The problem with parents is that their children know a lot about them after their birth, but only what their parents choose to reveal before. I will deal, as best I can, with the latter in this book. The former will have to wait until my memoirs.

My father was born at Burnham Market on 9th August 1920, the second son and middle child of Willie Rowland and Mabel Louise (née Bracey) His elder brother Brian had a grand set of names, “ Brian de Bracey Santry”. When my father’s turn came to be named perhaps the fun had worn thin, or maybe A.A. Milne’s comic knight Sir Brian Battleaxe had made an entry. Anyway he was simply “ William Barry”, although Barry was the family name of the Lords Santry. My father was in fact always called Barry rather than William. His younger sister’s name reverted to fantasy form, being called “ Bridget Domville”, the name of King Henry II’s fabled children’s nurse. Or perhaps she was named after the Bridget Domville who married the 3rd Lord Santry.

I was told nothing about my grandmother, except that she was a district nurse, doing her visits around Burnham Market by motorcycle. I have her leather biking gauntlets, which I use when driving my vintage cars. My father talked tenderly of her. She died of cancer when I was two years old.

The family lived at The Old Curiosity Shop, Burnham Market, Norfolk, just off the main green and rented for £22 p.a. The village is now known as Fulham on Sea, as it is mainly inhabited by week-enders in Volvos. It was quite a substantial house; it has now been divided into two or three dwellings, the largest being called “ Old Crabbe Hall”.

There my father and his siblings had the life of village children in the twenties and thirties, going to school in Fakenham by train.

I was told that my father won all the school prizes, and was also Victor Ludorum. Perhaps this was to encourage me. Unfortunately he caught a chill swimming for crates of oranges from a ship-wreck off Burnham Overy Staithe; this progressed to rheumatic fever and put an end to his sporting days. As a result he had a faulty heart valve and never ran again. He was also rated D4 in health checks, so at the age of 19 when war broke out, only made it to the Home Guard.

By then he was living with Sir Philip and Lady Gibbs, his aunt Agnes (née Rowland) He was working as a trainee publisher with Hutchinson’s, no doubt through the good offices of Sir Philip, who was one of their most successful novelists. Aunt Agnes died just before the outbreak of war, and my father stayed on with Sir Philip, whose own son and family left for America in 1940. Perhaps my father, described by Sir Philip as one of the world’s great laughers, kept his spirits up in those dark days, and possibly Sir Philip treated him as a surrogate child. He also probably helped Sir Philip keep aspirant second Lady Gibbs at bay.

They lived at Shamley Green, near Guildford, Surrey, my father travelling up to work by train to Hutchinson’s in Exhibition Road. He joined an amateur dramatic club in Guildford, and there met Joyce Cowdery, an art teacher at Tormead School.. They were cast together in “When we are Married” by J.B.Priestley as the young lovers, and, as they quaintly put it, had to make love on stage. My aunt Margaret was about 13 at the time and remembers having a fit of giggles watching them on stage, when she knew what was happening behind the scenes, so to speak. Emboldened by this they became engaged and were married on 21st August 1943 in Ascot. Joyce’s father had died a few weeks earlier; he had suffered from angina for some time. From a cine film of the wedding, my father, with his trademark moustache, and looking absurdly young, had Sir Philip as best man.

My mother was given away by her uncle Billie Mawle. Footnote 9. As the daughter of a bank manager and a very domineering mother, I think she tried to break away from these confines, studying art, at Oxford (at the pre-cursor to Oxford Brookes) and then at Reading University, for which she had a natural talent and lifelong enthusiasm, and generally revolting against her parents wishes. She even had a Nazi boyfriend-in the thirties! By all accounts Robert Bunsuch was true to form; he had a faceful of duelling scars, nicotine stained fingers and a Zvengali like power over my mother. He wrote closely argued letters about Germany’s need for Leibenstraum and National Socialism and told her father, Arthur Reginald, that he was being trained to take over the administration of British colonies in East Africa after victory for the Third Reich. This incensed my grandmother who always called a spade a spade, and told my mother “ If you marry Robert, we will have nothing more to do with you”. My grandfather grieved, but said nothing. My mother clearly had to make a difficult choice and cried for days. If she had followed Edward VIII’s decision, I would have had a very different life.

My parents took a flat at 84 Lexham Gardens, London, W8, to save that commute from Shamley Green. Sir Philip let them have the use of his son Anthony’s Austin Big Seven (Reg no GPL 293) to visit him at weekends. Out of nostalgia I have a similar model, which is now in Shetland. At the time it was the only car parked in Lexham Gardens; a policeman came round to request that it be garaged.

My mother had little experience of house keeping. Visiting the shops in nearby Stratford Road, she bought some sprats; not knowing weights she asked for 5lbs. They ate them continuously for two weeks, and never again.

84 D was the top flat, and whenever the air raid sirens went off my parents would go down to sit in the ground floor flat. One evening, for some reason, they sheltered outside in the hall, which was fortunate since an incendiary bomb went down the chimney and destroyed the ground floor flat.

My father had another lucky escape. One of his duties at Hutchinson’s was to look out for Doodle–bugs (V1 flying bombs) from the roof of the offices in Exhibition Road. One day, one appeared on the horizon; he thought if the engine cuts out now, we will be a direct hit. It did and my father started ringing the evacuation bell. Not leaving his post, his whole life was running before him. Until some ack-ack fire hit its ailerons and it veered off to the right, exploding near Gloucester Road Tube Station.

At this stage my parents moved to Peaslake to live in Sir Philip’s son Anthony’s house. My father still commuted to Hutchinson’s, and my mother stayed at home awaiting my birth. It was there, on Farley Heath, when the sky was jammed full of Lancasters setting off on one of the first thousand bomber raids over Germany that I decided I had had enough of these cramped conditions. My mother was rushed to Mount Alvernia Hospital in Guildford. I was born at about 11am on 18th July 1944.

I could go on in this vein for some time, but further events of my parent’s life, and my own will have to await my memoirs. I will also cover my children and grandchildren there. I will however tell the final story from Anthony Gibbs’ fantasy family tree. It is of course a true story.

My father’s sister Bridget (Biddie) was born in 1924. During the war she stayed at home, working in the NAAFI at Weybourne Camp, Holt and met a Canadian airman based there. They fell in love, became engaged and were married in 1945 in the church, in Prince Consort Road behind the Albert Hall, where my aunt Margaret sang in the choir. My father made all the arrangements, and my parents held the reception at their flat in Lexham Gardens.

Shortly afterwards he told Biddie he had to return to Canada for family reasons. Then came the bombshell. He wrote to Biddie saying he was already married with children. He was placed in custody by the Canadian authorities, who took a dim view of bigamy. Despite his protestations of love, he never returned to Biddie. She by then was pregnant and gave birth to a daughter.

She kept the child for six months, but then, possibly under pressure from my father, put her up for adoption.

Subsequently Biddie married John Ogden, who also worked at the Camp. He was prepared to bring up Biddie’s daughter as his own, but sadly by then the adoption process had been completed, and this could not happen. Biddie and John subsequently had their own daughter, Pennie, my first cousin and a good friend of the family. She and her husband Bob are helping me with this book.

But this sad vignette has had a happy ending. After the death of her adoptive parents, Biddie’s first daughter took steps to locate her natural mother. By then Biddie was in the early stages of senile dementia, but I remember her 80th birthday party, enjoying the occasion with her two daughters. Pennie has become good friends with her half sister, with whom she has a striking resemblance. I am delighted to have another first cousin.

The last three generations

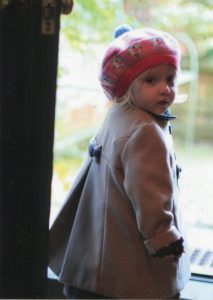

These comprise Richard Arthur Philip Rowland (born 1944) my children, Ben Alexander, Philip Barry (both born 1972) and Tessa Martha (born 1978) And Ben’s sons Johnnie Alexander and Arthur Jacob (both born 2007) Philip’s daughters Kristina Cherry (born 2007) and Victoria Tessa (born 2010) and Tessa and Richard Bonser’s daughter Dulcie Vaila (born 2014).

Footnote 4: Dr Cornelius John McKenna and Rev William John Rowland’s divorce

My great grandmother Annie Ellen Rowland (nee Domville) eloped with Dr McKenna in 1882 when he was Medical Officer for the Bengal 26th Native Infantry. After her divorce from Rev William John Rowland, they married in Marylebone in 1883. He became a Surgeon Lt Col in the Bengal Army and was retired and living at Beyres, Bayonne, France at his death in 1902.

His Will makes no provision for his wife; possibly they were estranged. It also seems likely that there were no children of the marriage, although Annie Ellen was only 30 at the time of her second marriage. The 1911 Census shows her living with her mother who died in 1914.

Annie Ellen died in 1932, being supported in old age by her daughter Lady Agnes Gibbs. I do not know whether she was ever reconciled with her other children.

Rev William John Rowland’s divorce

Jacky Fogerty has uncovered a newspaper report of Rev William John Rowland’s divorce from Annie Ellen Domville in 1881. We believed that he had spent some of his fortune obtaining the divorce. It now appears that he received damages of £400 from the co-respondent Dr Cornelius John McKenna. The report gives the evidence from the hearing-he was their doctor in India. In 1878 she admitted her misconduct to her husband, and he forgave her whilst staying at the Charing Cross Hotel. But she then eloped with Dr McKenna in 1881. Evidence was given by the manager of the Grand Hotel, Charing Cross that the couple “remained all night, occupying the same room, and left for Paris the next day”.

Clearly Charing Cross was a hotbed of passion.

Sir James Hannen directed the jury to award Rev WJ Rowland £400 damages and pronounced a decree nisi.

Footnote 5: Visit to the Bischofshof, Bad Honnef

On 10th June Philip and Melanie Gibbs and Richard Rowland replicated the visit in the 1920’s of Philip’s Great Grandfather Sir Philip Gibbs, and his wife Lady Agnes, Richard’s Great Aunt, to locate the so called “family schloss” of the Ditges family. Sir Philip was unable to find the “schloss”; perhaps if he had known in was the Bishop’s Palace he would have succeeded.

Of course our Australian cousin, Jacky Fogerty had already located it online, so our task was easy. Friederich Ditges, who was the agent for Germany and Switzerland for Rowland’s Macassar Oil, acquired the Bischofshof in 1825 when it was secularised. Alexander William Rowland visited it in the 1830’s and met his daughter Henriette; they were married in 1839. It remained in the Ditges family until 1917 when it became a school; in 1942 the Gestapo moved in, and in 2000 it became the IUBH-a privately owned international business school specialising in tourism management. It has 1800 students of which about 80% are German. All students live on the extensive campus in modern accommodation. Of the Bischofshof, only the gateway and the main tower remain. One of the rooms on the ground floor retains the original panelling.

Bad Honnef is said to house more millionaires than anywhere else in Germany. It is certainly a delightful old town, with winding pedestrianised streets and pleasant gardens fronting the Rhine. We cruised down past Rolandsect, site of Charlemagne’s palace where his general Roland was based. The past the site of the Bridge at Remagen to Linz where Philip and Melanie toured the town whilst I sampled the delights of a beer garden.

Later we visited the gothic fantasy castle Drackensfeld built by a banker who had financed the Suez canal. Apparently he never lived there.The cog railway goes up to the Drackensfeld mountain to a good newly constructed restaurant with panoramic views north to Bonn and south to Bad Honnef.

Visit by English descendants of the owners of the Bischofshof, Bad Honnef.

Richard Rowland and Philip and Melanie Gibbs are visiting the IUBH Business School, whose campus contains the Bischofshof, the family home of the Ditges family. In 1839, their relation, Alexander William Rowland married Henriette Ditges (see portrait) whose father Friedrich Ditges, a merchant from Cologne, had acquired the Bischofshof, after it was secularized in 1826.

The last attempt by the English family to locate the Ditges family home was by Philip’s relations Sir Philip Gibbs, the war correspondent, journalist and novelist and his wife Lady Agnes in the 1920’s. They had a drawing of the Bischofshof, but failed to find it. It is possible that by then the building had been altered. (see photo) Thanks to the internet it is now easy to locate.

Alexander William Rowland was the proprietor of Rowland’s Macassar Oil, a business founded by his grandfather in about 1800. It made and sold one of the first hair oils and was credited as being one of the first nationally advertised products. (see advertisement) Like the Hoover, its name became associated with the product. By the 1840’s the hair oil was being used by the Royal Family and nobility of England, as well as by several sovereigns and courts in Europe. The business was sold to Beechams, now part of Glaxo Smith Kline, in the 1940’s.

Alexander and Henriette lived in London and had eight children. Henriette died in 1851 giving birth to a daughter, Henrietta who became a celebrated social reformer and founder of Hampstead Garden Suburb and the Dame Henrietta Barnett School for Girls in North London. So Henriette’s name lives on.

Footnote 6: Henriette de Bellegarde’s first marriage

The ever resourceful Jacky Fogerty has discovered that another Ancestry user, BrianFreeman15, who seems to be descended from the second husband of Henriette de Bellegarde’s mother, has found Henriette’s divorce record from her first husband Julius Rudolph Erckens, and uploaded it to his public Bouwen Tree.

Ironically it has been sitting there in the UK High Court of Justice divorce proceedings, Erckens v Erckens, final decree 1 Nov 1887. We had not found it because we thought she was probably divorced in France.

Brian Freeman’s has tracked down Henriette’s (English) mother and sister Eugenie (who was a witness at Henriette’s wedding to William Domville Rowland) and documented their lives in England.

There is an article in the London Evening Standard which gives a colourful account of Henriette’s life with her first husband as follows:

High Court of Justice… Probate and Divorce Division (Before Sir J Hannen) Erckens v Erckens – This was a petition presented by the wife, Henrietta Eliza Suzanne Erckens, praying for the dissolution of her marriage on the ground of the cruelty and adultery of her husband, a chemical manufacturer. Mr Middleton said in 1880 the Petitioner was living in London with her parents, and the Respondent, her cousin, came on a visit. The parties became engaged, and they were married in Saxony before the Burgomaster. They lived in Saxony till 1882. The Respondent then took out emigration papers from the German Government, and the parties so doing were prevented from living in Germany afterwards except as visitors, and in no case longer than two years. They some time after that took up their residence in England, but at the latter end of that year, 1882, they went to Mexico in order to look for employment. Nothing resulted from that visit. In November 1883 they again returned to England, and after a short residence the Respondent went to Vienna, where he remained until 1884. The Respondent left his wife at Vienna, where her mother resided, and returned to London. About Christmas that year the Respondent started for New Orleans, with the hope of getting employment at the Exhibition, the Petitioner being again left in England. In 1885 he again returned, and he and the Petitioner took up their residence at Hammersmith. The Respondent again went to New Orleans, but before he came back to this country last year she discovered that he had been on improper terms with a Madame Perron, and the present suit was instituted…case stood over

Jacky found a record for Rudolph Erckens travelling to New Orleans at the right time.

The above article mentions that her husband was her cousin, so Jacky looked at her mother’s family and has given a condensed version of a complicated story, which has interesting echoes of the Rowland story, as follows:

Matthew Urlwin Sears and his wife Susanna Caroline Smartt had an engraving and publishing business in St Pancras and by 1861 also had a country residence in Edmonton Middlesex. They seem to have had three children. Daughter Harriet Sarah married a German from Burtscheid Aachen in the Rheinland, Gustav Adolph Rudolph Erckens (called Rudolph) in 1851 at St Pancras Church – probably a trade connection of her father’s. In 1853 he was a banker in Paris and signed legal documents to terminate his partnership with his father Johann/Jean, who had died, and make Harriet Sarah his partner. Shortly after, son Julius Rudolph (also called Rudolph) was born, apparently in Paris, and subsequently the family was back in Burtscheid Aachen having more children, whose birth and baptism records are on Ancestry with mother’s and father’s full names. A sister of Gustav Adolph Rudolph, Julienne, has descendants in the US with a family tree on Ancestry.

At some stage another daughter of Matthew and Susanna, Caroline Prudence Sears, somehow made her way from London to Gibraltar, where she married Jean Alexandre Paulin Niboyet on 25 Oct 1856. This is conveniently set out on a Geneanet page for the Niboyet/Mouchon families:

This also has a fine Niboyet/Mouchon family tree and two articles about Jean Alexandre’s activities as a French Consul and an author/playwright and a photo and summary about his mother from Wikipedia (fascinating family!).

Caroline and Jean Alexandre had two daughters, Henriette and Eugenie, but all did not go well and there was a divorce petition from him in London in 1863, co-respondent Chapotin. This did not result in divorce, but a subsequent petition from Caroline, alleging adultery and not defended, resulted in a divorce finalised on 26 January 1880. A media report incorrectly states that there were no children from this marriage, despite the evidence of other official documents and the Geneanet page.

After the divorce, Caroline immediately married an entrepreneur called Charles Waller and both her daughters are living with them in the 1891 Census, Henriette under her maiden name. Ancestry had garbled both names and put them down with surname Waller, which is why they were not showing up on searching. Caroline died in 1893 and “Henriette Elise Susanne Erckens singlewoman” was her Executrix. Caroline was buried in St Pancras chapel, possibly a traditional burial place for the Sears family. Poor Eugenie did not marry and ended up as a servant to a bricklayer’s family in the 1911 Census, a very sad end.

Meanwhile, Jean Alexandre also quickly remarried, to a German woman, Stephanie Leser (there are good records for her family in Germany on Ancestry), and they had two children. The daughter, Pauline Niboyet Dubois, became a naturalised US citizen in New York in 1936 and died in 1937, in the US or France. She married Daniel Otto Lutten, and their granddaughter is Claire Juliette Beale, my new third cousin.

We do not know what happened to Julius Rudolph Erckens after the divorce. The article goes on to say that in 1887 he was helping his new lady friend, Madame Perron, with her glass engraving and silk painting business in Lambeth.

Footnote 7 – Cecil Edmond Rowland

He was a younger brother of Rev William John Rowland who went to South Africa and disappeared. Very little known about him, there is the story that he returned once arriving at Waterloo Station, as thin as a skeleton with only a parrot and shotgun as baggage. The family knew something was amiss when he stopped collecting his allowance in Johannesburg.

But once again Jacky Fogerty has come to our rescue-she has unearthed his Death Certificate from the Belgian Congo. He died aged 36 on 23 November 1913 in Elisabethville. Described as” celibataire” and a “peintre”. So no South African cousins to discover.

Footnote 8

The First World War years of Sydney Domville Rowland; an early case of possible laboratory-acquired meningococcal disease. See “The First World War years of Sydney Domville Rowland: an early case of possible laboratory-acquired meningococcal disease“. By Peter Wever and A J Hodges. Published by group.bmj.com April 2016.

Footnote 9: N.W.R.(Billie) Mawle

I was recently re-reading Sagittarius Rising by Cecil Lewis describing his adventures in the Royal Flying Corps in WW1. I remember my grandmother always wore her brother’s RFC “wings’ badge with pride. I googled him and found out that he was also a WW1 fighter ace. This was the time when new recruits to the RFC had an average life of three weeks. He started with Se5 squadron 84 in Northern France on 17 July 1918. By 8 August, three weeks later he had 12 successful hits, amazingly shooting down 3 Fokkers (sic) on one day; he was then severely injured and invalided out. In November 1918 he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Uncle Billie was always kind to me giving me a 21st present of a sturdy leather suitcase with my initials on the side-we now keep dressing up clothes in it-later he gave me a leather writing case, also with my initials. At Cambridge I used a portable British Empire typewriter from his factory in Birmingham. I am sorry I never had the opportunity to hear his war stories. He came to my wedding on 25 September 1971 but died three months later.

My cousin David Pollard recalls two stories Uncle Billie told him.

The first that when many families lost sons in WW1, all the Mawle sons survived, and were castigated as being unfairly lucky. Clearly this had a great effect on Uncle Billie.

Secondly when training your airmen he used to tell them that the joystick was not important. And to prove this, when flying he would terrify them by throwing it out of the plane. Don’t worry, he told David, I always carried a spare!

I loved reading about your/our family and seeing the pictures of Barry, Joyce and you as I remember you all well. I also remember having seen the short wedding video where my grandfather Billie gave your mother away. I would very much like to have a copy if that would be possible, please? I have some Mawle video clips ( but taken in the 1950s) and it would be nice to start with the one of your parents’ wedding with Billie Mawle.

Re the Nazi boyfriend – someone told me ( maybe Elsie or Gwen?) that he had been at a weekend house party where he had been so infuriated at losing a game of tennis that he stormed off the court, and that was the crunch time ( when either Elsie gave her ultimatum or Joyce saw him for what he was).

Another memory I have is my mother telling me that Margaret ( I think it was ) was once so angry with her husband for his lack of appreciation for her Sunday roast that she poured it, with all the gravy, over his head.

I will now carry on reading. Well done everyone involved in putting this family story together.

love

Vanessa

Thanks for all your comments-I will try to locate the 8mm film of my parents wedding at Ascot.

Perhaps Margaret can corroborate the stories about tennis and Sunday lunch-I have not heard them.

In fact and perhaps not unsurprisingly I hardly knew of the Nazi boyfriend who was not a good loser-Margaret has been my source there.

I will pass your email address to Rachel who can tell you about her emigration plans

All best

Please contact me because I am writing a book on the voyage of HMS Tortoise to Australia and NZ 1841-3 and on which Henry Jones Domville was the assistant surgeon.

regards

Don

NZ

Hi Don

He was on my wall for many years-really the most I know about him is in my online text and trees

All best

Richard

Hi Richard,

Henry Jones Domville was recorded in a journal as having sketched a few drawings while in New Zealand on HMS Tortoise in 1842-3. If you have any clues as to how I might track them down I would be most appreciative.

All the best

regards

Don

No-sorry.Have you tried the Domville Family Tree web-site? Are you in touch with them?

All best

Richard

Hi Richard,

Yes, I have been in touch with the Dumville/Domville website and supplied information for it. I’ve included my website – it has a search box and is very large, so anybody who might know anything about Henry Jones Domville can go there and if necessary get in touch with me by my email on the site.

All the best

regards

Don